Home » Publications » Could International Reference Pricing “Go Viral” After COVID-19?

ISPOR Conferences – November 2020

Could International Reference Pricing “Go Viral” After COVID-19?

Source: ISPOR.org

Felix Wolfrum, MSc, Department of Applied Natural Sciences, TH Köln – University of Applied Sciences, Cologne, NRW, Germany; and Vasco Pontinha, MPharm, MA, Department of Pharmacotherapy and Health Outcomes, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Pharmacy, Richmond, VA, USA

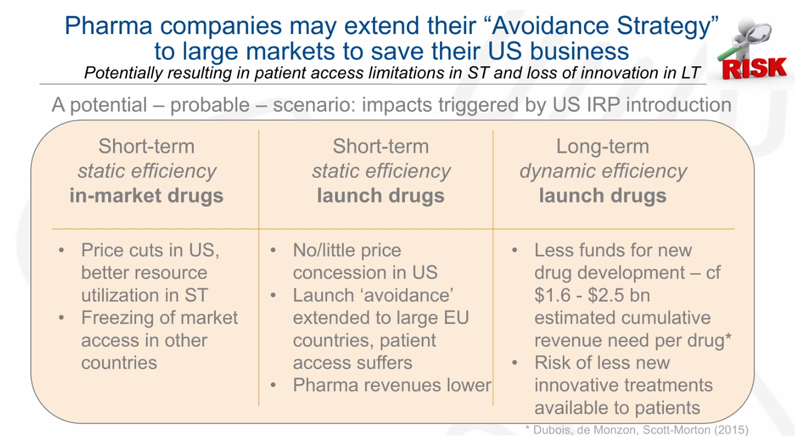

With a short introduction to international and external reference pricing, Andras Incze, PhD, MBA, Healthcare Management, Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University Germany and Akceso Advisors AG, Basel, Switzerland, moderated this breakout session, highlighting international interdependencies in pricing to show the inequality in availability and price equivalence concerning the countries’ GDP (gross domestic product). For example, it is widely known that the United States registers the highest drug prices in the world. With COVID-19, there is an appetite to implement an international reference pricing system in the United States. Figure 2 shows a likely scenario, which ultimately can result in avoidance of large markets to save pharmaceutical companies’ business in the United States. As Incze pointed out, this creates a clear problem of patients’ access, irrespective of willingness to pay.

Picking the “Right” GDP

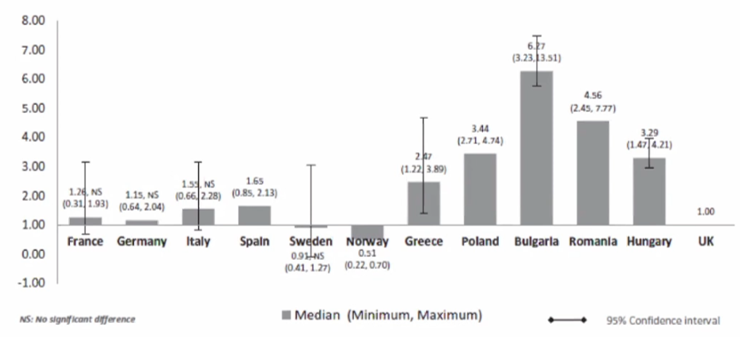

Little evidence is available about the effects of international reference pricing, especially in low- and middle-income countries. According to Jaime Espin, PhD, Andalusian School of Public Health, Granada, Spain, this leads to a cumbersome assessment of the impact of international reference pricing compared to other pricing methods. However, Espin discussed how GDP adjusted prices for drugs are still comparatively higher in low- and middle-income than in high-income countries. (Figure 3).

Consequently, when establishing price references, countries should select countries with equivalent GDP. In addition, establishing comparators with equivalent GDP as references can help countries with the price negotiation. Nevertheless, Espin argued international reference pricing is not a panacea and only as good as its implementation.

"Powerful countries must push for an equitable and fair differential pricing and distribution of those treatments and vaccines." - Zoltán Kaló

A View on Price and Value

For Zoltan Kalo, PhD, Semmelweis University; Syreon Research Institute, Budapest, Hungary, the answer was clearly “winners and losers.” From his perspective, lower-income EU countries seem to be at a disadvantage with an EU-wide-price for drugs.

The concern is that what is a good value for money in a high-income country is mostly not a good value for money in a low-income country. As with any other commodity, prices need to be adjusted to the internal economic status. The implementation of value-based pricing therefore requires country-specific prices. Widespread use of international reference pricing does not lower prices in low-income countries. Zalo argued that it results in limited patient access to drugs. This is particularly relevant and urgent in the context of a global pandemic and access to vaccines and treatments for COVID-19, since global problems can only be tackled with global solutions. Therefore, powerful countries must push for an equitable and fair differential pricing and distribution of those treatments and vaccines.

Innovation Versus Access: A Tradeoff

For the United States, the urgency is to clearly decrease the level of healthcare spending (currently 18% of GDP is spent in healthcare). Consequently, Louis P. Garrison, PhD, The Comparative Health Outcomes, Policy and Economics (CHOICE) Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, talked about how the United States intends to reduce that expenditure by implementing an international reference pricing system. The consequences of such an implementation remain unclear given patchwork of payers at a federal and state level that exist in the United States. Considering the significantly high costs of drug development, Garrison discussed the resulting trade-off: innovation versus accessibility? Creating a drug development monopoly may lead to a greater supply of new drugs in the long-term, but reduced access to those drugs in the short-term. This is crucial because in the current pandemic, dynamic efficiency (ie, eliciting the optimal rate of innovation over time) should be the main goal. According to Garrison, the implementation of an international reference pricing system in the United States will result in higher prices and poorer access in other countries, with a possible worse situation in the United States.

When asked about whether increasing price transparency between countries minimizes the impact of international reference pricing, Garrison discussed how increases in transparency will likely result in the irrelevance of international reference pricing and the need for differentiated pricing in general. A different perspective was provided by Espin, who argued that, “increases in price transparency would not result in a reduction in differentiated pricing, as it is almost impossible to compare net drug prices.”

"Creating a drug development monopoly may lead to a greater supply of new drugs in the long-term, but reduced access to those drugs in the short-term." - Lou Garrison

All panelists agreed that the use of international reference pricing system is a complex subject and its implementation, especially during a global pandemic, should be differentiated and adjusted to the context of each country.